Over 10M+ Customers Served

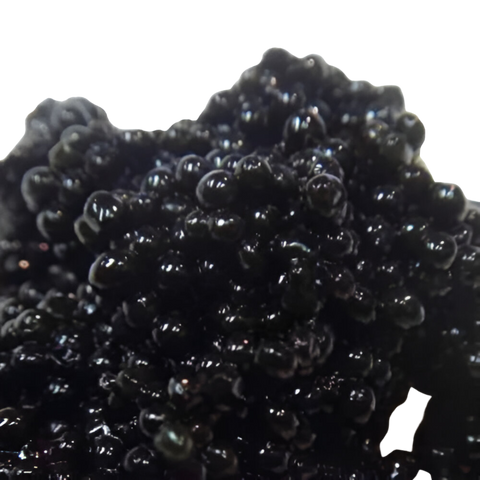

Best caviar

Bemka is my go-to place for high quality caviar and other luxury foods. They have a wide variety of caviar to choose from, and each one is more ... Read More

Bemka is my go-to place for high quality caviar and other luxury foods. They have a wide variety of caviar to choose from, and each one is more delicious than the next. Customer care is top-notch. They're knowledgeable about the products and always willing to assist me with my order. I send family and friends the gourmet gift baskets for special occasions and everybody loves them!

Read LessErin Lynne

Verified Buyer

Amur Kaluga Caviar

Shop now

My go to

I’ve been ordering caviar from Bemka for the last few years and my guests always love it. The quality has been consistent and I’ve had a good ex... Read More

I’ve been ordering caviar from Bemka for the last few years and my guests always love it. The quality has been consistent and I’ve had a good experience with customer service . I absolutely recommend!

Read LessCamila Giraldo

Verified Buyer

Kaluga King

Shop now

Great caviar and service

Absolutely amazing caviar! The quality is top-notch, and Sahar is the best—super knowledgeable and always provides excellent service. This is th... Read More

Absolutely amazing caviar! The quality is top-notch, and Sahar is the best—super knowledgeable and always provides excellent service. This is the only place I get my caviar now. Highly recommend!

Read LessKatherine Hughes

Verified Buyer

Classic Russian

Shop now

Amazing quality

I ordered from Bemka for the first time and I have to say the product was on point, on time, and the customer service people went above and beyo... Read More

I ordered from Bemka for the first time and I have to say the product was on point, on time, and the customer service people went above and beyond helping me all my stupid little questions. They are amazing!

Read LessNaisha Joseph

Verified Buyer

American Salmon Roe

Shop now

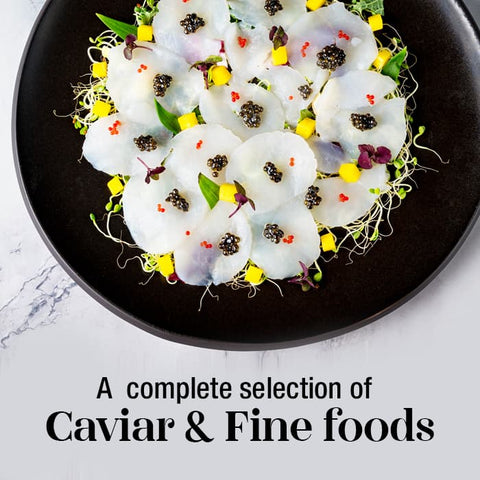

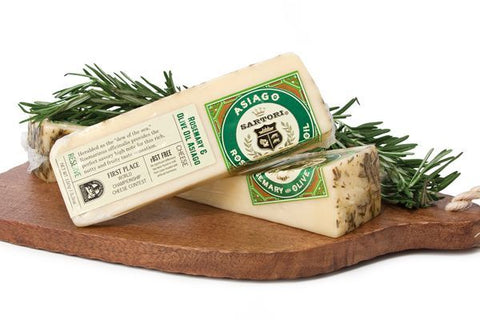

About our products

At Caviar Lover, we proudly present an opulent selection of the finest caviar for sale that promises to satisfy the most discerning palates.

Blog posts

Overnight Shipping

40 Years

Customer Service

Sustainability

Sign up for our newsletter

Get exclusive discounts and announcements.